Data centers are the invisible engines of our digital world. Every Google search, Netflix stream, cloud-stored photo or ChatGPT response passes through banks of high-powered computers housed in giant facilities scattered across the globe.

These data centers consume a staggering amount of electricity and increasingly, a surprising amount of water. But unlike the water you use at home, much of the water used in data centers never returns to the water reuse cycle. This silent drain is drawing concern from environmental scientists. One preprint study (not yet reviewed by other scientists) from 2023 predicted that by 2027 global AI use could consume more water in a year than half of that used by the UK in the same time.

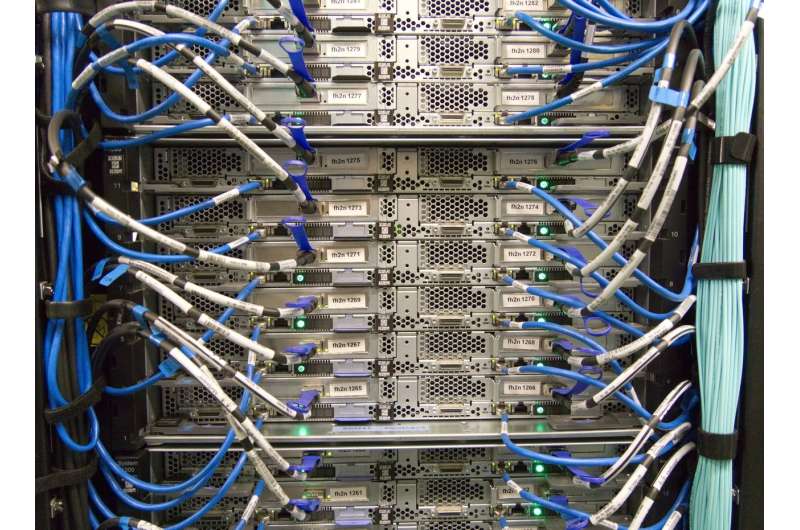

Data centers typically contain thousands of servers, stacked and running 24/7. These machines generate immense heat, and if not properly cooled, can overheat and fail. This happened in 2022 when the UK endured a heat wave that saw temperatures reach a record-breaking 40° Celsius in some areas, which knocked off Google and Oracle data centers in London.

To prevent this, data centers rely heavily on cooling systems, and that’s where water comes in.

One of the most common methods for cooling data centers involves mechanical chillers, which work like large fridges. These machines use a fluid called a refrigerant to carry heat away from the servers and release it through a condenser. A lot of water is lost as it turns into vapor during the cooling process, and it cannot be reused.

A 1 megawatt (MW) data center (that uses enough electricity to power 1,000 houses) can use up to 25.5 million liters annually. The total data center capacity in the UK is estimated at approximately 1.6 gigawatts (GW). The global data center capacity stands at around 59 GW.

Unlike water used in a dishwasher or a toilet, which often returns to a treatment facility to be recycled, the water in cooling systems literally vanishes into the air. It becomes water vapor and escapes into the atmosphere. This fundamental difference is why data center water use is not comparable to that of typical household use, where water cycles back through municipal systems.

As moisture in the atmosphere that can return to the land as rain, the water data centers use remains part of Earth’s water cycle – but not all rain water can be recovered.

The water is effectively lost to the local water balance, which is especially critical in drought-prone or water-scarce regions – where two-thirds of data centers since 2022 have been built. The slow return of this water makes its use for cooling data centers effectively non-renewable in the short term.

The rise of AI tools like ChatGPT, image generators and voice assistants has made data centers work much harder. These systems need a lot more computing power, which creates more heat. To stay cool, data centers use more water than ever.

This growing demand is leading to a greater reliance on water-intensive cooling systems, driving up total water consumption even further. The International Energy Agency reported in April 2025 that data centers now consume more than 560 billion liters of water annually, possibly rising to 1,200 billion liters a year by 2030.

What’s the alternative?

Another method, direct evaporative cooling, pulls hot air from data centers and passes it through water-soaked pads. As the water evaporates, it cools the air, which is then sent back into server rooms.

While this method is energy-efficient, especially in warmer climates, the added moisture in the air can damage sensitive server equipment. This method requires additional systems to manage and control humidity, which necessitates more complex data center design.

My research team and I have developed another method which separates moist and dry air streams in data centers with a thin aluminum foil, similar to kitchen foil. The hot, dry air passes close to the wet air stream, and heat is transferred through the foil without allowing any moisture to mix. This cools the server rooms in data centers without adding humidity that could interfere with the equipment.

Trials of this method at Northumbria University’s data center have shown it can be more energy-efficient than conventional chillers, and use less water. Powered entirely by solar energy, the system operates without compressors or chemical refrigerants.

As AI continues to expand, the demand on data centers is expected to skyrocket, along with their water use. We need a global shift in how we design, regulate and power digital infrastructure.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Citation:

AI is gobbling up water it cannot replace. I’m working on a solution (2025, June 16)

retrieved 16 June 2025

from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Leave a comment