Origins: A Daughter of Two Worlds

Born in the early 19th century, Efunsetan Aniwura came into a world shaped by conquest, trade, and migration. Her roots lay deep in the turbulent soil of the collapsing Oyo Empire, at a time when Yoruba towns were being reshaped by war, politics, and commerce.

Her father, Chief Ogunrin, hailed from Ikija—one of the smaller but notable Yoruba settlements near modern-day Abeokuta. Her mother was from Ile-Ife, a sacred city revered as the spiritual homeland of the Yoruba people. This bi-regional parentage connected her both to the martial traditions of Ogunrin and the cultural prestige of Ife.

As a young girl, Efunsetan witnessed the fall of Ikija to Egba forces during the internecine Yoruba wars. Her family fled the ruin, relocating to Ibadan, a city that had risen as a war camp and was rapidly transforming into a new Yoruba power center. Ibadan offered not just shelter, but opportunity. For a girl like Efunsetan, who grew up helping her mother trade kola nuts and local goods in the market, Ibadan’s rapid expansion was fertile ground for ambition.

The Rise of a Merchant Matriarch

What separated Efunsetan from other women traders was not just business acumen—it was vision. She understood the scale of commerce, the flow of goods across rivers, markets, and empires. Unlike most women who sold produce or beads, she diversified into the transatlantic economy.

By her twenties and thirties, she had built an interregional trading network dealing in tobacco, palm oil, shea butter, cotton, and slaves. She controlled dozens of farms. She had storehouses stocked with rare goods. Some records suggest she traded directly with Europeans via the coastal ports of Badagry and Porto Novo, moving luxury items and agricultural goods. Her products, notably the local textile known as Kijipa, reached as far as the Americas.

At her peak, she was said to own over 2,000 slaves—not just for labor, but as business agents, field hands, domestic aides, and sometimes security enforcers. She ran her household with military efficiency. Slaves were cataloged, monitored, and frequently rotated among her properties.

In the context of 19th-century Yoruba society, slavery was deeply embedded, yet Efunsetan’s use of slaves reflected not merely the norms of the day but a fiercely hierarchical mind. She was not merely rich—she was a controller of people and process, an industrialist in the age of oral tradition.

Iyalode of Ibadan: Power in a Male Domain

In a city dominated by warlords and male chiefs, Efunsetan achieved what few women even imagined—she was appointed Iyalode of Ibadan, the highest possible political position for a woman.

The Iyalode title wasn’t honorary. It carried legislative power, access to council meetings, and influence over community affairs. Traditionally, the Iyalode represented all the women of a city before its rulers—protecting their economic rights, voicing their concerns in court, and participating in high-level decision-making.

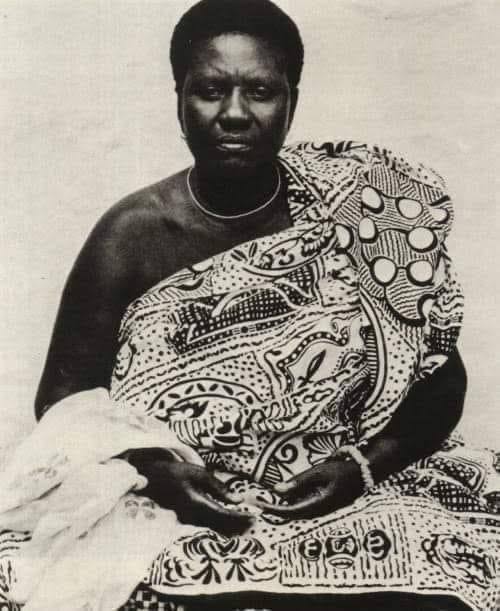

Efunsetan’s elevation to this post wasn’t given—it was earned. She was respected (and feared) by the male chiefs, not only for her wealth but for her strategic mind. She bankrolled warriors during wars. She lent money to chiefs, and rumors swirled that even military campaigns were funded from her coffers. She wore iron bangles like a male warrior and moved with an entourage.

As Iyalode, she defied the unwritten rule that women were to serve in the background. She sat with men, judged cases, and influenced policy. But her style was imperial. She was authoritative, and she made few attempts to soften her presence. Many men bristled.

A Mother’s Grief, A Tyrant’s Reign

Behind Efunsetan’s steely mask lay a wound that never healed: the loss of her only daughter.

Historical records suggest her daughter died during childbirth in the early 1860s. After this, Efunsetan never bore another child—a fact that haunted her deeply. In Yoruba culture, fertility was not just a private concern; it was a marker of legacy, spiritual favor, and societal worth.

This grief intensified by her enormous power, transformed her into a harsh, even brutal ruler. She reportedly enacted a law across her estate that no female slave was to become pregnant. If they did, both mother and man responsible were executed. By some accounts, over 40 slaves were killed under this law.

To the outside world, she became a tyrant—intolerant of weakness, cruel to subordinates, obsessed with control. But to her close allies, these actions stemmed from psychological torment. The death of her child made her view pregnancy as betrayal—an insult to her loss, a reminder of what she could never regain.

In African feminist scholarship, some researchers argue that Efunsetan was both victim and villain—a woman punished by a patriarchal world for being childless, and who in turn punished others through rigid dominance.

Enemies at Court: The Aare Kakanfo and the Final Betrayal

While her power grew, so did her enemies. Chief among them was Aare Ona Kakanfo Latoosa, the de facto head of the Ibadan military and civil authority.

Latoosa had built his political empire through violence and tactical alliances. He saw Efunsetan not as an ally, but a threat. She had money, a public voice, and a disobedient streak. Unlike other chiefs’ wives or traders, Efunsetan did not defer. She resisted his policies and undermined his war taxes. She even insulted him in public.

This tension came to a head when a domestic incident in her compound led to a formal complaint. Efunsetan had executed one of her slaves in a particularly gruesome manner. Though common in aristocratic households at the time, Latoosa seized on this as grounds to remove her.

She was summoned to the council. Charges were read. Fines were levied. But Efunsetan, proud and uncompromising, refused to show humility. She paid the fines but would not apologize. This enraged the council.

Latoosa then took a step further. In a clandestine move, he reportedly bribed her adopted son, Kumuyilo, with money and political promise. On the night of June 30, 1874, two of her slaves entered her chambers while she slept. They strangled her. Her body was buried before dawn.

Efunsetan Aniwura died not as a queen in glory, but as a matriarch assassinated by her own house.

Aftermath: Myth, Memory, and Meaning

The news of her death shocked Ibadan. The people, especially women, mourned her loss. Markets closed. Songs were sung. But officially, the city moved on. Latoosa faced no penalty. Kumuyilo vanished from records.

Yet Efunsetan’s legacy endured—not just in history books, but in folklore, drama, and even rebellion. Yoruba oral tradition transformed her into both martyr and monster. In some tales, she is the wicked slave-owner who killed pregnant women. In others, she is the brave woman who stood up to corrupt men and died for her courage.

In modern Nigeria, her story has become a powerful allegory for female autonomy, political jealousy, and the dangerous intersection of power and grief.

Representation in Modern Culture

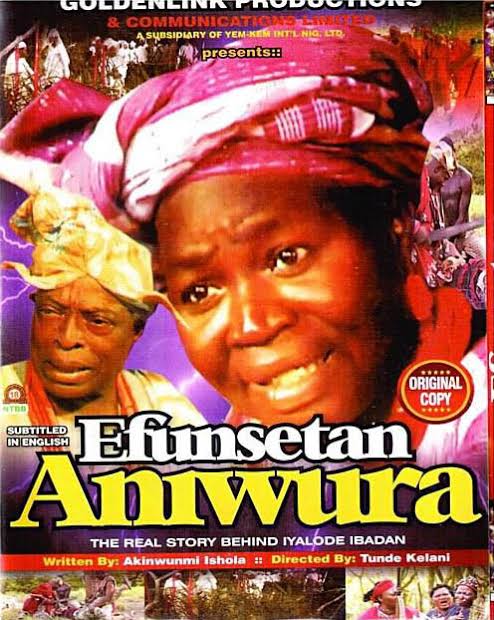

Efunsetan’s life has inspired plays, poems, and films. Most notably, the Nigerian playwright Akinwunmi Isola dramatized her life in the stage play Efunsetan Aniwura, which portrayed her in a sympathetic light—as a powerful woman undone by patriarchy and personal tragedy.

The 2005 Yoruba-language film Efunsetan Aniwura, directed by Tunde Kelani, further amplified this image. In these artistic portrayals, her complexity is foregrounded: neither hero nor villain, but a tragic figure whose world punished women for wielding the power of kings.

In Ibadan today, a statue of Efunsetan stands at Challenge Roundabout. Sculpted in bronze, it shows her in regal pose, eyes fixed forward, iron bangles gleaming. It is a rare tribute to a woman who lived by her own rules, loved fiercely, ruled brutally—and died because she refused to kneel.

Leave a comment