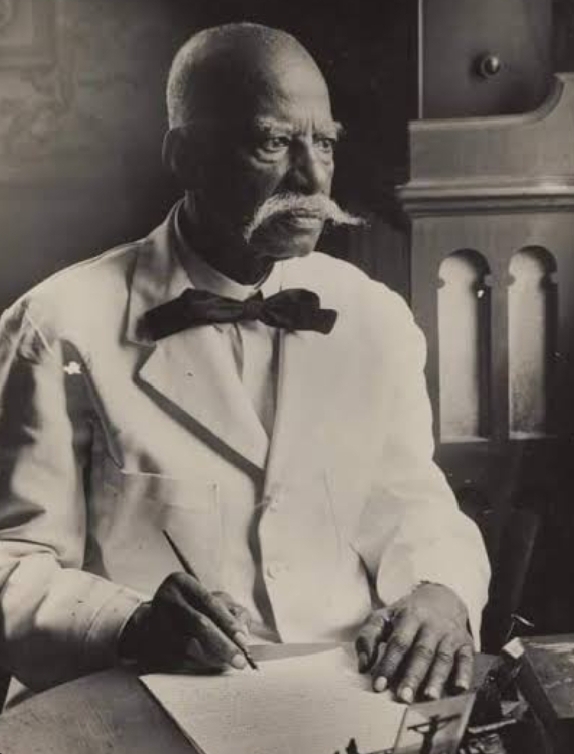

In colonial Lagos, one Yoruba Oba dared to speak when silence was expected. His name was Oba Eshugbayi Eleko, a king whose quiet defiance unsettled the British administration and stirred the hearts of his people.

What followed was not just a crisis—but a confrontation that changed the meaning of kingship under empire.

This article tells that story.

The Rise of a Quiet Contender

Born in the mid-19th century into the royal Dosunmu family, Eshugbayi Eleko was not the most likely candidate to ascend the Lagos throne. He was the son of Oba Dosunmu, the king who signed the 1861 treaty ceding Lagos to Britain under duress. Educated but deeply rooted in Yoruba tradition, Eshugbayi carried the burden of a legacy that included both royal prestige and the humiliation of colonial submission.

In 1901, following the death of Oba Oyekan I, Eshugbayi was selected as the next Eleko of Eko (Oba of Lagos). His selection was widely welcomed among Lagosians, particularly among traditional elites and the growing class of educated African nationalists. But even from the early days of his reign, tensions between colonial authority and indigenous power structures loomed large.

The Water Tax Controversy: Public Health or Colonial Exploitation?

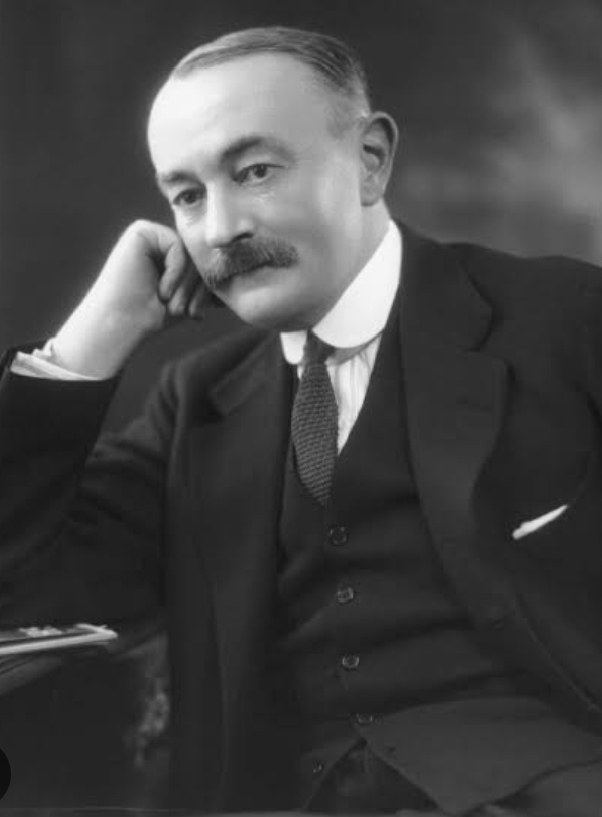

The first major test of Oba Eshugbayi’s leadership came in 1908. The colonial government, under Governor Walter Egerton, introduced a £130,000 water scheme to pipe clean water into Lagos. While the project was hailed in official circles as a public health initiative, it came with a sting: a “water tax” imposed on Lagos residents to fund it.

For most Lagosians—many of whom used private wells and did not request the water system—the tax felt punitive, elitist, and disconnected from their daily reality. Oba Eshugbayi voiced what many were already thinking. He opposed the tax on moral, cultural, and economic grounds, arguing that the water project disproportionately benefited European residents and wealthy Africans, yet placed financial strain on the broader populace.

His opposition was not quiet. He mobilized chiefs, community leaders, and market women. Massive protests followed, with nearly 15,000 Lagosians marching to Government House. It was one of the earliest coordinated urban protests in colonial Nigeria. The streets were filled with placards, chants, and speeches—not against the water itself, but against taxation without consultation.

The colonial government responded with hostility. The protest was dismissed as backward and uninformed. British officials viewed Oba Eshugbayi as a troublesome figure—too popular, too outspoken, and too unwilling to play the role of ceremonial collaborator.

The Battle Over Muslim Authority (1919)

By 1919, the Lagos monarchy under Eshugbayi was no longer just a traditional institution—it had become a symbol of cultural autonomy. That year, a conflict erupted between the colonial administration and the Oba over the appointment of Muslim leaders at the Lagos Central Mosque. The British, who had grown accustomed to manipulating Christian Yoruba elites, now sought to control Islamic institutions through administrative oversight.

Oba Eshugbayi, who understood both the religious and political weight of Islam in Lagos, made a series of appointments that bypassed colonial vetting. For the British, this was unacceptable. For Eshugbayi, it was a matter of indigenous authority.

The Governor’s office reacted by withdrawing formal recognition of Eshugbayi’s kingship. His official stipend was revoked. The message was clear: toe the line or lose your throne.

Yet what followed shocked the colonial establishment. Far from crumbling under financial pressure, Oba Eshugbayi received support from Lagosians across ethnic and religious lines. Donations came from market women, Muslim clerics, and even Christian professionals. The people sustained him. His court, though no longer officially recognized, continued to function as the emotional and political center of Lagos. It was a rare show of mass political solidarity in an era of colonial fragmentation.

Exile by Ordinance: The Dethronement of 1925

By the mid-1920s, Governor Graeme Thomson had grown increasingly intolerant of Eshugbayi’s influence. A combination of his earlier protest record, his interference in religious appointments, and his refusal to be an ornamental figure led to the ultimate colonial backlash.

On 6 August 1925, under the powers of the Native Authority Ordinance, the colonial government issued a decree formally removing Eshugbayi as Oba of Lagos. He was ordered into internal exile—far from the coast, in Oyo town, to prevent political agitation. The act was presented as administrative necessity. In truth, it was a silencing.

The Lagos public was outraged. Mass prayers were held. Traditionalists wore mourning cloths. Nationalist groups condemned the act in newspapers like The Lagos Weekly Record. But the colonial machine was unmoved. Eshugbayi was forcibly relocated, watched by guards, and banned from any communication that could stir civil unrest.

It was the first time a Yoruba Oba had been dethroned not for criminality or misrule, but for challenging state authority on behalf of his people.

The Legal Battle and the London Appeal

In a remarkable turn of events, supporters of Eshugbayi Eleko launched a legal counterattack. Led by Nigerian lawyers and Herbert Macaulay, often called the father of Nigerian nationalism, the Oba’s legal team filed a suit against the colonial government, arguing that his removal had violated traditional rights and colonial law alike.

The case escalated through multiple layers of colonial courts before finally reaching the Privy Council in London—the highest court of appeal for colonial subjects. The hearing took years, during which Eleko remained in exile, and a regency was installed in Lagos.

In 1928, the Privy Council issued a landmark ruling: it held that the colonial Governor had indeed exceeded his legal authority by dethroning the Oba without due process or sufficient cause. Although the decision did not mandate an automatic reinstatement, it was a political victory. It shattered the myth of absolute colonial legal power and signaled that indigenous authority had standing—even in the Empire’s highest courts.

The Triumphal Return: 1931

By 1931, a new Governor, Sir Donald Cameron, arrived in Nigeria with a less antagonistic view of traditional institutions. Recognizing the deep legitimacy Eshugbayi still held among Lagosians and the cost of continued political resentment, Cameron initiated negotiations for a peaceful resolution.

In October 1931, Oba Eshugbayi Eleko was officially allowed to return to Lagos. The city erupted in celebration. Thousands lined the streets to welcome him back. Market women wept openly. Drummers and chanters sang oriki (praise poetry) in his honor. It was not simply a king’s return—it was a moment of cultural resurrection.

Reports say that the emotional toll overwhelmed the Oba. As his subjects lifted him onto a throne-shaped carriage, tears streamed down his face. He fainted momentarily—his body catching up with the weight of history.

Final Year and Death (1932)

Eleko resumed his position, not as a passive monarch but as a symbol of resistance, legal triumph, and the enduring relevance of Yoruba traditional authority. His remaining months on the throne were marked by peace and spiritual affirmation. But he was aging.

On 24 October 1932, barely a year after his return, Oba Eshugbayi Eleko died. His burial at Iga Idunganran, the royal palace in Lagos, was attended by tens of thousands. He was succeeded by Oba Falolu Dosunmu.

Legacy: What Eshugbayi Eleko Means for Nigeria

Oba Eshugbayi Eleko’s life and dethronement were not isolated events. They were part of a larger movement—a growing resistance to colonial intrusion into the cultural, religious, and political lives of indigenous Nigerians.

His reign became a blueprint for what was possible: that a traditional monarch, grounded in legitimacy and public respect, could serve not merely as a cultural figurehead but as a moral anchor in turbulent times.

1. Legal Precedent

His appeal to the Privy Council remains one of the earliest successful legal challenges by a colonized African leader against the British Empire. It set a standard later followed by nationalist figures in Ghana, Kenya, and South Africa.

2. Cultural Empowerment

Eshugbayi’s legacy affirms that Yoruba kingship, when properly aligned with the people, is not just ceremonial. It can be socially and politically transformative.

3. Model for Resistance

He was neither a military hero nor a revolutionary—but his defiance reshaped colonial policy and inspired a generation of educated nationalists. Men like Nnamdi Azikiwe, Obafemi Awolowo, and Herbert Macaulay found in him a living example of principled resistance.

Final Thoughts: The Crown That Refused to Bow

When we remember Oba Eshugbayi Eleko today, it is not only as a dethroned monarch. He was a man who understood the sacred duty of Yoruba kingship—not as a tool of the state but as a voice for the people. In defying the colonial government, he paid a personal price—exile, humiliation, and constant surveillance. But in doing so, he forced open the doors of colonial law, shifted the narrative around African leadership, and reminded the world that dignity is not a gift—it is a right.

In an age where many traditional rulers are co-opted or silenced, the legacy of Eshugbayi stands tall: a crown can carry not just beads and titles, but justice.

Leave a comment